1800-1900: Struggling against Censorship

The 19th century was the century of the nation state. The once so proud Dutch Republic began it under the rule of a French king: Louis Napoleon, followed in 1813 by a prince of the House of Orange: King William I. The new monarchy was confronted with the demands of the liberal movement. Republican sentiments could also be heard, though not from the masses.

The liberal breakthrough in 1848 led to a regularization of the freedom of the press. New political movements appeared on the horizon: Socialists demanded an honest share for the workers or even a classless society. A balancing act was required between the increasing power of the state and the liberal legislation on the freedom of expression, one of the most important buffers against censorship.

The mechanical printing press began to play a major role from around 1870 onwards. Material printed on cheap wood-based paper became much more affordable. Advances in technology, rapid population growth and legislation to ensure better schooling and literacy all helped to create a large reading public. In 1869 the abolition of the Dagbladzegel (a tax on daily newspapers), which had been regarded by many as censorship, allowed the newspaper to begin its development into a modern mass medium.

The 19th century produced a colourful company of figures who tested the boundaries of the new freedoms. Anarchists, communists, sensation journalists, pornographers: they all made use of the mechanical printing press and vied for the attention of the general public. In particular, the rising socialist movement and Abraham Kuyper's Anti-Revolutionary Party made strategic use of the (printing) press to disseminate their ideas.

Throughout Europe the governments began, in more moderate or extreme ways, to prosecute unwelcome groups. In the Netherlands this was through the courts, while in Germany for instance the Anti-Socialist Laws were the main instrument.

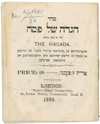

This period of nationalism saw opponents targeting the symbols of the nation state such as 'the King' or 'the Army'. Religious confession was a major divisive element at the edges of Europe. In particular Jews in Eastern Europe were seriously threatened in their existence and freedom of expression. They resisted this trend by continuing to publish their own texts and works in semi-illegal organizations.