Anarchists in court, England, April 1945

Introduction

During the last difficult months of World War II, four anarchists were prosecuted by the British authorities on the suspicion of having disseminated ideas that might incite members of the armed forces to desert. While the Allied victory was almost certain, the English authorities wanted to make clear that discipline would be maintained until the final shot had been fired.

'To cause disaffection'

In November 1944 the police raided several homes and the London offices of Freedom Press, the centre of the anarchist press in England. Arrests followed on various grounds. During this raid the police confiscated a typewriter, printed material, including a circular letter, and issues of the journal War Commentary. John Olday was among those arrested. In the studio of Philip Sansom, who was arrested somewhat later, Olday had set up a small printing plant, where he used a manual press to produce the circular letter to the soldiers, as well as booklets featuring his cartoons and individual prints. The Prosecution had prepared the case carefully. Searches of the kits of privates Taylor, Pontin, McDonald, and Ward revealed copies of the circular letter and War Commentary. These were used as evidence that the opinions expressed in these publications were being disseminated within the armed forces and had a subversive effect there. On Thursday 22 February 1945 the police arrested Marie Louise Berneri, John Hewetson, and Vernon Richards, all involved in War Commentary, in connection with this case.

On 10 March they were arraigned, together with Philip Sansom. Olday stood trial in an entirely different case. All four were accused of having: '... conspired together and with other persons unknown to endeavour to seduce from their duty persons in His Majesty's Service and to cause among such persons disaffection likely to lead to breaches of their duty.'

On 17 April the trial started in 'the Old Bailey' and was continued on 23 April. The proceedings were a model of English courteousness. Mr Justice Birkett stated that [while] 'the views expressed might seem strange to many people[,] he was quite ready to believe that they were actuated by high motives.' Because the arrests had caused quite a stir, and ample funds had been collected for the defence, solicitors had been retained that could hold their own against the prosecutor in the judiciary. Counsel John Maude K.C. spoke for three full hours at the opening hearing. The defence did not deny that the material had been produced. After all, it had been seized and lay in full view of the court. Rather, the defence denied that it had been intended to achieve an effect on the readers, as this was basically what Defence Regulation 39A required.

John Olday had not sent his circular letter out at random but had obtained the names of military personnel receiving the letter from Freedom Press, which published War Commentary and kept a list of interested individuals. Understandably, the majority of these interested were sympathetic to anarchism or even embraced anarchist ideology. Equally understandably, at the end of World War II, the 3.5 million members of the British armed forces included some anarchists. Most were in fact conscientious objectors assigned to non-combat reserve units. This information turned out to be available elsewhere as well. The person conducting the investigation, Detective Inspector William Whitehead, knew exactly where to go. He searched the kit of Sapper Colin Ward and interrogated him on the Isle of Orkney, where Ward was stationed at the time. The matter appears to have been serious enough to justify travelling to this remote island to prove 'seduction' and 'disaffection'. The problem facing the prosecutor was clear. How do you prove that a text leads to 'seduction' and 'disaffection', when nobody has deserted proclaiming: 'I'm leaving the army because of this or that article in War Commentary and the Circular Letter'?.

The four servicemen whose kits were searched, when questioned at the hearing, vehemently denied that reading this material had had the slightest influence on them. And the suspects strenuously denied any attempt to cause disaffection. The charade astonished some. In Guy Aldred's the Word, this attitude was condemned as hypocritical, although the reproach was probably based on a lot of longstanding grudges on the part of this old timer from the anarchist movement. Moreover, this strategy was effective only to a certain degree. The jury found the three men guilty all the same. The judge, who emphasized repeatedly throughout the trial that the men were not on trial for their views but for violation of 39A, handed down a relatively mild sentence. Hewetson, Richards, and Sansom were sentenced to nine months in prison. The maximum term of imprisonment for this offence was 15 years.

While the sentences could have been far longer, nine months was still serious. Marie Louise Berneri, as the wife of Vernon Richards, was not convicted. She was acquitted on the ground that a husband and wife could not legally conspire with one another. The trial drew a lot of attention. The gallery was filled with comrades, as well as with all kinds of mysterious high-ranking military personnel. The police inspected the identity cards of seemingly random visitors, immediately instigating an outcry in England at the time. Many English were offended by the very idea of having to present proof of identification in some places. They also found it to be in very poor taste that the authorities used this concentration of anarchists and their sympathizers to identify and arrest individuals who might have committed political offences.

Support

Disclosure of the arrest of Hewetson, Berneri, Richards, and Sansom quickly instigated in uproar in the English press. Questions were asked in the House of Commons as well. On 1 March 1945 Conservative MP George Strauss asked Secretary of Home Affairs Herbert Morrison, a member of the Labour Party, whether confiscating a typewriter was legal, and whether raiding such a club in that manner was reasonable. The Secretary responded that the typewriter was evidence. As to whether the actions were reasonable, he stated: 'I appreciate that the anarchist movement in this country is small and uninfluential, but, on the other hand, the prima facie evidence of the kind of activity it was conducting, indicated the possibility of serious offences.'

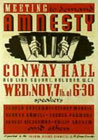

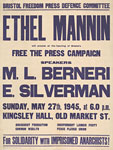

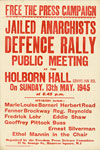

The press perceived the entire affair as an infringement on freedom of expression. On 10 March 1945 War Commentary ran an appeal to form a Freedom Press Defence Committee. Herbert Read chaired this committee. Fenner Brockway and Patrick Figgis were deputy chairmen. Ethel Mannin agreed to serve as secretary and S. Watson Taylor as treasurer. The committee was remarkably active. A protest meeting was soon convened on 15 April. Herbert Read was one of the main speakers there and did not mince words. He conveyed the widespread sentiment as follows: 'We will fight; fight the Defence Regulations and that foul and un-English institution, the political police.' Additional meetings were held on 13 May, following the conviction, and on 16 June. After the trial the committee was renamed the Freedom Defence Committee and remained active until 1948. The committee shifted its efforts to cases concerning conscientious objection and political repression within the armed forces. Well-known activists within the committee included Harold Laski, Bertrand Russell, and George Orwell. The committee published the Freedom Defence Committee Bulletin.

Conclusion

In the issue of 5 May 1945 War Commentary raised the question of who had ordered the trial. Was it Secretary Herbert Morrison? Or Secretary of War P.J. Grigg? The fact that none other than the attorney general led the prosecution suggested that people in high places were involved. Many of those involved have speculated about this. Could the trial have been intended as a warning to the war-weary troops? This might be inferred from the extensive consideration the prosecutors gave to texts relating to soldiers' councils. According to another theory, communist foe Morrison tolerated War Commentary for a few years as a useful anti-communist voice amid the reverberations of sympathy for the communists that had arisen among the left, after Hitler invaded the Soviet Union. By the spring of 1945 this voice was no longer needed, and the time had come to silence it. In his autobiography, however, Morrison made no mention whatsoever of the case. Or was the impending revolution in Greece making the authorities nervous? The fact remains that anarchists, who numbered but a few hundred in England, and their periodical War Commentary, with a circulation of only 4,000, received massive publicity thanks to the trial. Leading newspapers featured anarchist texts verbatim in millions of copies. In this sense, the government strategy was counterproductive.

In addition, the government sorely miscalculated the reaction of public opinion. Despite the ongoing casualties, even in April 1945, the public did not want the government to stifle criticism of the war from radical and in many cases anti-militarist sources. People whose views were controversial to say the least had widespread popular support, as exemplified in an open letter dated 23 February 1945 and written by an illustrious group of writers, including T.S. Elliot and E.M. Forster: 'when these actions from the authorities are allowed to pass without protest they may become precedents for future persecutions of individuals or of organisations devoted to the spreading of opinions disliked by the authorities.' Freedom of the press is possible, only if it is generously supported and accommodates all opinions, popular and abject ones alike. This was indisputable to opinion leaders in England in 1945 and, war or no war, important enough to justify speaking out.