Short chronicle

15 and 16 April

The death of Hu Yaobang, former secretary of the Chinese Communist Party, is the occasion for public mourning and demonstrations at the campus of Beijing University. Hu Yaobang was known as a reformist who had advocated the rehabilitation of victims of the Cultural Revolution. He was dismissed from his post for being "soft" in 1987. The students' sorrow turns into a call for democracy and freedom of the press. This ushers in a series of daily demonstrations, not only in Beijing but in other Chinese cities as well. In China, demonstrating for political purposes is considered as unusual behavior and a dangerous challenge to the authorities.

22 April

About 200,000 students and onlookers are present at the memorial service for Hu Yaobang in the Great Hall of the People. It becomes clear that emotions other than pure grief are prevalent. On a paper wreath for Hu, the words "Democratic Soul" are placed. After demonstrating the students do not return to university. An "autonomous student federation" is established (20 April) that aims at an enduring public dialogue with the authorities. To win the sympathy of the public, the students proceed with strict discipline. Violence and chaos are to be avoided by all means. The crowds in the streets grow steadily, and people are still wary.

27 April

The People's Daily of April 26 published a devastating editorial comment inspired by China's leader Deng Xiaoping. It accused the students of attempting to create turmoil. This would undermine the leading role of the party. Autonomous student organizations were deemed illegal. The students respond by organizing a demonstration in protest of this editorial comment. This demonstration surpasses all previous demonstrations in size and character. The public expressly backs the students by donating money and drinks. Such massive protest, a people's movement with students representing the people, had never occurred in China before. The authorities refuse to negotiate with the autonomous student federation. Off the record they do speak with representatives of the moderate student organizations.

4 May

The 70th anniversary of May 1919 is celebrated. Seventy years ago more than 3000 students demonstrated at Tianan'men Square against the weak attitude of the Chinese government towards the imperialist superpowers. A political movement and a wave of strikes resulted from this demonstration. May 4, 1919 marked the coming of age of students and intellectuals as an independent political power, the conscience of the nation. A massive meeting May 4, 1989, commemorates this, and hundreds of journalists ostentatiously join in. Demonstrative marches take place in other Chinese cities as well.

10 May

About 10,000 students, writers, and journalists demonstrate for freedom of the press. During this demonstration the head band is introduced, following similar demonstrations in South Korea and Japan. The demonstrators ride their bikes because their destination is on the outskirts of the city: the headquarters of the People's Daily. After this date, the bike is no longer used for demonstrations because it goes too fast and the public cannot show their feelings of solidarity. Moreover, bicycling reinforces the impression of chaos.

13 May

The announcement of a hunger strike by 200 students drastically changes the character of the demonstrations, although the demands remain the same: public dialogue and acknowledgment. The Square is now permanently occupied by students. The public reacts by organizing solidarity meetings with the hunger strikers. The strike causes disruption in the movement, as many people fear that the situation would get out of control. Party leadership is also divided. Unlike the other leaders, party secretary Zhao Ziyang favors a dialogue with the students and deems their demands reasonable. The students are careful not to become a subject of political machinations.

15, 16, and 17 May

The number of demonstrators keeps growing. An official visit by the Russian president Gorbachev ensures optimal media coverage of the demonstrations in both the Chinese and foreign press, despite the fact that officials organize a detour to avoid the presence of Gorbachev in the Square. Demonstrations are held according to an established pattern. The demonstrators act as representatives of a working unit, viz. the company or organization they work for. They carry a banner identifying this unit. One person usually carries a sign or an object, such as a puppet, stating the demands. A town crier, usually a woman on a bike, shouts the slogans. The rest would follow. People with head bands are clearly distinguishable as officials responsible for order.

18 and 19 May

Zhao Ziyang, the party secretary, and prime minister Li Peng separately visit ill students on hunger strike in the hospitals and students in the Square. Zhao, the most reform-minded among the party leadership, begs the students to finish the hunger strike. "I am old and you are young." His tears herald his own demise. He will spend the rest of his life under house arrest. Li Peng, the hard liner, loses his patience and once again refuses to have a public dialogue with the students. Caricatures posted all over the city picture Li Peng as Adolf Hitler. On 18 May, Gorbachev leaves China, departing from Shanghai, and that same day the number of demonstrators grows to one million.

19 and 20 May

At midnight, martial law is announced by Prime Minister Li Peng. From now on, demonstrations are explicitly illegal. The students stake out the square, civilians can no longer freely wander about. With its demarcated small streets and dwellings for the delegations, the square resembles a village. Sympathizers from Hong Kong have donated tents. The Command in Defense of the Square is now established, and the moderate student leader Wu'erkaixi is removed from the leadership. The students announce the end of their hunger strike. As the struggle rapidly becomes polarized, the hunger strike no longer seems to be a sufficiently coercive measure.

21 May

Martial law means imposing a ban on demonstrations. The demonstrations of working units calling for reform are now prohibited, but the public in Beijing cannot be denied access to the streets. From now on, the inhabitants of the city function as a cordon sanitaire protecting the students at the square. Intervention of the army seems inevitable and civilians flock to the streets at night to confront the invasion. Barricades are made out of buses and fences. Army units on their way from the outskirts of Beijing to the center are successfully halted by the public. Many of these recruits come from Beijing themselves. The role of the masses in the streets has become vital and the atmosphere is tense.

30 May

The Goddess of Liberty is erected at the square. The statue was made by students of the Arts Academy. Many students from other cities have come to Beijing these days to camp at the square. The army has occupied the railway station in order to stop the inflow. In Hong Kong sympathizers demonstrate in millions. The Autonomous Workers Association of Beijing is established and its three leaders are immediately arrested. Army units are put up in the suburbs. The students now demand an end to martial law, the withdrawal of troops and the reassurance that there will be no punishments afterwards.

3 and 4 June

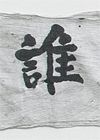

The 27th Army, consisting of storm troops from the province of Hebei, invades the city. Up to this time, the masses in the streets felt sure that Chinese soldiers would never kill their compatriots. This is proved to be a delusion. The conflict now begins to resemble the defense of the free citizens of Beijing against an invading army of strangers. Tanks and armored vehicles are burnt, soldiers are killed. The citizens face fearful odds, and the majority of victims are civilians in the streets surrounding the square. The students leave the square in a funeral march in the early morning of 4 June. Some of them sing the International. The Goddess of Liberty is hacked down by the army. A black banner saying "Where are the souls of our Heroes?" can be seen hanging at the gate of the Foreign Languages Institute.