THE ARTS OF ONESELFtwenty six short tales on personal memorabiliaText by Tjebbe van Tijen - Photographs by Akiko Tobu |

|

My hand is already over the waste basket when suddenly I hesitate: maybe I shouldn't? This time I keep it, many more times I throw away things, still, over the years, my house is filling up with objects and documents that have survived the ordeal of being classified as waste; things I keep on to for later... to help me remember. These are often things not purposely produced as memoralia like souvenirs, picture post cards or photo snapshots, but objects to which I give personally an extra meaning, changing their category from daily life utensil to personal treasure. There is a story with each of such objects, in most cases the story is not visible, the object does not depict a particular event, the event needs to be told. Language to make "the invisible visible" says Krzysztof Pomian in his study on the 'Origin of the museum' and he invents a special word for such objects that have changed their status, from an object with use value to an object representing what can not be seen. The term Pomian uses is 'Semiophors', based on the Greek words for 'sign' and 'carrier'. (Pomian/NB 82) There are others with a similar observation as Pomian using different words like the art historian Mieke Bal: "Objects are inserted into the narrative perspective when their status is turned from objective to semiotic, from thing to sign.." (Bal/NB 2) These memory objects, these personal memoralia mostly relate to those who are or were dear to us, family, friends, lovers or those admired by us. First of all bodily things: umbilical cord, foreskin, hair of children or lovers; the first teeth in a box; nails; blood, semen and lipstick traces on love letters; garments from first baby dresses to ladies underwear; shoes and handkerchiefs; scarfs and hats; spectacles and artificial teeth. Quiet recently, while cleaning a cupboard, I discovered the blood stained chemise that marks the birth of my daughter when she was first held by her mother. I tried to compromise and make a picture of it before throwing it away, but the end of the debate that followed was that this object has been taken from my custody and thus might be saved for posterity. There are of course those things we inherit, often things that have lost their practical use and can not yet be classified as 'antique', things not kept for their price or prestige, but for emotional reasons, because they help us remember. Of course valuable objects can very well function as personal memoralia, but their status is different, potentially they belong to the markets of gold, silver, jewels, antique, art and other things that 'have a price', they can be exchanged for money and money can be exchanged for one's wishes or needs and the needs and wishes of the day are often the strongest.

Objects that have purposely been made for recollection,

like the souvenir, seem to be of another order. Susan Pearce, who is often

quoted in recent literature on collecting, notes that in this case "the

object is prized for its power to carry the past into the future" and that

"the collector does not attempt to usurp its cultural and historical identity"

(Pearce/NB 15) Be it mass produced trivialia from holiday resorts or the

work from local artisans, the owner will still have a personal recollection

when seeing or showing this object. So also here the object is a trigger

for personal narrative. The souvenir belongs to the tradition of pilgrimage,

bringing back home relics, prove of a long travel, often something for

which there is a claim of direct contact with a holly person or place,

something with super-natural power. The ease and comfort of modern transport

do not compare with the hardship of pilgrimage in former times but the

souvenir is still a relict, a carrier of some of the qualities of the 'holy

land'. Graceland is an example of a modern pilgrimage place. Here each

year 15 to 20 thousand devotees visit the tomb of Elvis Presley. John Windsor

an art journalist and specialist in transcendental meditation, researched

the trade in Elvis relics, he mentions the Graceland Enterprise Inc that

exploits "the ownership in perpetuity of the Elvis 'image'", a "legalized

form of immortality", selling Elvis tee-shirts, badges and other memoralia

for a value of 15 million dollars a year. There is also the "undercover

trade" in "Elvis necrophilia" with "toe-nail clippings, warts, even Elvis

sweat preserved in glass phials", supposedly distilled from a stage floor

covering on which Elvis perspired copiously. Windsor describes a greeting

card that claims to carry drops of Elvis sweat with the text: "Elvis poured

out his soul for you, and NOW you can let his PERSPIRATION be your INSPIRATION."

Both official and unofficial Elvis markets describe their wares as souvenirs,

but as Ward notes "it is the quality of devotion that turns an Elvis souvenir

into an Elvis fetish." Elvis has made gospel records with Christian content

and in some of his films poses as an almost Christ like figure. After his

death his legend has grown to saint like proportions. Seen in the tradition

of the christian saints Elvis has become a 'myroblyte,' "a saint whose

relic exudes a myrrh, oil, balm or liquid" which "beneficially is used

for the uplifting of spirits and the healing of bodies". Elvis has joined

ranks with holy persons like Saint Nicholas and Saint Menas. The historian

Charles W. Jones writes in great detail on this subject in his study 'Saint

Nicholas of Myra, Bari and Manhattan, biography of a legend' (Jones...).

He describes how pilgrims over many centuries visit the grave of Saint

Nicholas in the Italian town of Bari, "to carry away a droplet or a phial"

of the 'myrrh' from the body of Nicholas "to their faraway home". Jones

observes, "Pilgrims are insatiable collectors of souvenirs, talismans,

and artifacts in every age" and notes that because the body of Saint Nicholas

was emanating this liquor continuously (each day a priests goes into the

crypt in Bari to tap), it could be bought also by "those of meagre purse".

(University of Chicago Press; 1978; p.66-67) Another parallel with modern

tourism and the souvenir industry is the pillage and plunder in previous

centuries of sacred objects of far away and foreign cultures, to be taken

home as booty, to be sold, stored and put on show in the treasure rooms

of temples and palaces, in the private Curiosity Cabinets/Wunderkammers,

or the state museum, an act expressing both contempt and interest for that

what is strange and foreign. Tourist industry has transposed this love-hate

relationship to modern times through the mass production of representations

of the authentic, adapted to what tourists are supposedly expecting. Plunder

of artifacts has developed into plunder of cultural values, mimicking forms

of expression and ways of life that have disappeared already or are in

a high stage of disintegration. Group travel and strict time and space

management by tour operators do allow for little interaction with local

population to get some understanding of living style and conditions of

the local population. Often such contacts are not even desired by either

side. In the end, on the day of departure, there is always the airport

shop which will, in exchange for the left over local currency, supply a

nice choice of 'personal' memoralia. Some object, at least, is needed for

later, to help us remember. Was it not so that we were travelling because

we wanted to construct a special memory, to give some more meaning to our

life, or when a trip was for business reasons we still tried to acquire

some material proof of our contact with an other culture?

There are also objects that are not typical for

a certain region or country, but still emanate some kind of longing or

nostalgia for far away times and places that did not even exist. Miniature

rustic houses, small models of indistinct fishermen boats, glass spheres,

with and without snow flakes, showing minuscule landscapes. There has always

been an industry that produces what some call 'tat'. John Windsor gives

a definition of what 'tat' objects represent: "not what the past was really

like, but what customers like to think it was like" in other words "today's

picture of yesterday". (John Windsor "Identity Parades"; p55) Bad taste,

stereotype, kitsch, tat, the too well educated will force themselves not

to acquire such detestable objects, though maybe inwardly, there is something

left of the open mind of a child, a strong attraction to still have such

taboo things. One of the explanations of the origin of the word 'kitsch'

is, that it is of German origin and derived from the verb 'kitschen' (den

Strassenschlamm zusammenscharren) meaning to collect rubbish from the street.

It associates also with the spontaneous activity most young children show,

when they start to pick up, be it in the house, street or field, anything

they fancy for 'their collection', stones, sticks, feathers, leaves. Throwables

from others and nature become collectibles for a kid, who will enjoy discovering

similarities, comparing them, grouping them, arranging them in attractive

displays, showing them to others, often with small stories and explanations.

The organized recycling of throwables, the jumble

sales, flea markets, and bazaars attract many 'grown-ups'. Here this 'childish

thing' is made somewhat acceptable, because it is packaged as trade, but

aside of the impetus of making a good deal, finding something cheap, the

main fascination is remembering. Such a chaotic displays of goods stimulate

our abilities for recollection, they are collective memory theatres with

their mish-mash of obsolete utensils, kitsch and tat, waiting to become

someone's symbol for a moment of someone's life. For the last three decades

I live next door's to the Amsterdam flea market, so I have had ample opportunity

to study this phenomena. One aspect that seems very relevant to personal

memoralia is the daily ordering of goods on such a market, its spatial

taxonomy. There are the very organized stalls with second hand shoes only,

black boots, brown boots, sandals neatly lined up, but also what is called

the floor displays,straight on the pavement, of things from all times and

classes thrown together by the fate of the day. I associate this with an

early discussion on changing the display of the art collection of the Austrian

Emperor Joseph II at the end of the 18th century, when one of the early

public museums in Europe was created. Though there is quiet a difference

between the junk on a flea market and an imperial art collection, the discussed

principle remains the same. Before the reorganisation of the gallery by

Christian von Mechel, a graphic artesian and art dealer, all different

periods and styles, without much order, were associatively arranged in

the different exhibition rooms. Mechel introduced a system of strict grouping

of the paintings and sculptures according to different schools and a chronological

time line. In a study on this debate the Dutch art historian Debora J.

Meijers summarizes the debate of that time: "Mechel's opponents () did

not wish () to take on such a preconceived division of the works in the

gallery. Rather they preferred to rediscover such order or classification

for themselves, each time they viewed the paintings." (Debora J. Meijers

"Kunst als natuur de Habsburgse schilderijengallerij in Wenen omstreeks

1780; p.212) 'Rediscovery' is the word and many collections of personal

memoralia are, consciously or not, arranged in such a way. Formal chronology

is mostly absent. Objects of a different order are spatially arranged,

often juxtaposed to create an aesthetical effect. Of course there are people

who will compulsively line up anything that comes under their hands, and

the bookkeepers of the family with their strict chronological photo albums,

but I dare to say that in most cases creative chaos is the preferred system

for personal memoralia. The shoe box archive with a mix of personal papers

and photographs is one of the best examples of this practice. Each time

a document is searched for, each time something is shown, a new disorder

of the content of these boxes will be established. It is a bit different

from reshuffling playing cards because there is not a complete remix, certain

strata of document tent to stay together. Such messy containers are a stimulus

for new associations, new comparisons, new ways of recollecting the stages

of one's life, they are very much a model for the way we remember....

The personal snapshot, the photograph with which

we try to capture the unique and spontaneous moments of our lives, is the

most massive produced memory device of our time. Though the snapshot is

mostly seen as a pure pictorial device, belonging to the realm of the visible,

its social function is strongly narrative. When you are shown pictures

by friends, even by complete strangers you happen to meet, there will be

explanations and stories. As you follow with your eyes the finger of the

narrator pointing at details and you listen to the stories it is striking

how many references there are to what not can be seen in the picture itself.

It is often boring for others to look at the pictures we took, because

we see so much more in them, or better trough them, we are recalling what

remained outside the frame, what happened just before or after, smells,

temperature, atmosphere, aura... It is evident that the photograph remains

the most popular device for recollection, film, sound, and video recording

have never been even near to take over its role. One reason for this is

what the Hungarian collector of amateur snapshots Sándor Kardos

calls the greatest power of photography: "the experience of the moment".

Kardos compares the photograph with a time based registration like film:

"In a film one needs a construction, not only in space but also in time.

It is necessary to invent a succession of moments. There is never the spontaneous

natural impulse of a still photograph." (Kardos/Horus Archives) Kardos

is a man whose collection of amateur snapshots has grown to over 200.000

examples arranged in boxes using 120 different categories of his own making

like 'people appearing with things they are proud of or would like to obtain',

'with weapons', 'performing indecent activities', 'in unusual dress', 'wearing

masks' and 'unexpected things happening at the moment of exposure'. By

collecting, selecting, classifying and arranging photographs from other

people, sometimes knowing the creators, sometimes not, the function of

these snapshots is changed from a personal memory utensil to a carrier

of aesthetic values. Seen with other eyes, put in an other context new

meaning is constructed. Pictures of moments of many different personal

lives, torn from their particular time line, reassembled in series chosen

by the artist archivist Kardos who says he is "making photographs by finding

them". Taking away the original context, the process of collection, selection

and labelling reveals something the photographs originally did not show:

the recurrent themes, the archetypical element in these pictures.

It's a century ago that George Eastman came up

with a photographic film that was more light sensitive and produced on

a roll so multiple pictures could be taken easily. "You press the button,

we do the rest" was the slogan that changed the status of photography from

a stiff posing, 'the head on stare' in front of a fixed camera on a tripod,

to the informal amateur 'snap shot'. It meant that the professional photographer,

still wearing the artist cape of the portrait painter of previous centuries,

largely went out of business and had to survive by becoming a shopkeeper,

selling photo equipment and supplies. On this retailers network an ever

growing world wide photography business rose, and with the rising of the

industry, prices of camera, film and prints were falling with the throw-away

camera, for one time use, as the lowest point. Photographs have become

"items of passing interest with no residual value to be consumed and throw

away." (Tag/The burden of representation; p.56) This quote on the changing

use of photographs has been published only ten years ago and now, with

the advance of digital imagery, not only the use of photographs, but also

the photograph it self will become more volatile and dematerialized. Optical

film will be replaced by electronic memory card, and the visual display

of television set and home computer will enable instant melting of frozen

moments. Zapping through the television channels and surfing over the Internet

will be followed by similar navigation strategies for our electronic family

album; as long as our spinning hard disks do not crash and picture storage

standards remain compatible with the ever faster changes of computer software

and hardware. There will still be a need for tangible objects, the photograph

as a print, especially because of its portability, but the progressing

miniaturization, from desk top to palm top, will decrease the amount of

enduring memory devices. "The electronification of memory provides another

twist how societies do indeed remember their past in an extraordinary changing

present" notes the sociologist John Urry and he quotes a colleague Huyssen

who describes the influence of television with their "politics of quick

oblivion" and "the dissolution of public space in ever more channels of

instant entertainment". This "frenetic pace of change" leads to "the collapsing

belief in possible futures" and results in "a kind of collective amnesia".

Urry and Huyssen conclude that in a reaction people try "to slow down information

processing" to "resist the dissolution of time.. to claim some anchoring

space in a world of puzzling and often threatening heterogeneity, non-synchronicity

and information overload". (John Urry/'How societies remember the past'

in 'Theorizing museums'; NB 72)

We seem to race forward on the tracks of time

in a straight line but when we want to remember, to reflect, we have to

look back, and as a train in a curve the past will show itself briefly,

and further away we can dimly see the rails disappearing in the landscape.

When I try to explain remembering and the passing of time, spatial metaphors,

like the previous one, are the first thing that come to my mind. 'Looking

back' and 'in retro-spect' are commonly used notions. In his personal memoir

"Present Past - Past Present" Eugène Ionesco writes: "Up to the

age of thirty-five, one could look back at the valley that one has come

from. But now I am going down the other side and the only valley that awaits

me is the valley of death. The mountainside separates me from myself."

Such spatial metaphors for time and remembering are not completely satisfactory,

there is a lot of emphasis on continuity, the flowing or passing of time,

as if time is passing us, as if we are advancing through it. All euphemisms

for our own vulnerability, as if time is passing out, were in fact we are

passing away. Time travel would be the reversal of such flowing of time,

as if each instant in time had been kept in a historical reserve and could

be revisited. The French philosopher Henri Bergson is one of the critics

of this conception of time: "time should not be conceived spatially and

memory is to be viewed as itself temporary, as the piling up of the past

on the past, no element is simple present but is changed as new elements

are accumulated from the past." Bergson wrote this at the beginning of

this century and his ideas had a great impact. One of the persons inspired

by him was the French writer Marcel Proust, who besides being his student,

was a cousin of his wife. Proust's most famous novel series 'A la recherche

du temps perdu' () is constructed on the theories of Bergson, who was putting

emphasis on man's creative abilities and intuition as an instrument for

understanding the universe. "Yes: if, owing to the work of oblivion, the

returning memory can throw no bridge, form no connecting link between itself

and the present minute, if it remains in the context of its own place and

date, if it keeps its distance, its isolation in the hollow of a valley

or upon the highest peak of a mountain summit, for this very reason it

causes us suddenly to breath a new air, an air which is new precisely because

we have breathed it in the past, that purer air which the poets have vainly

tried to situate in paradise and which could induce such profound a sensation

of renewal only if it had been breathed before, since the true paradises

are the paradises we have lost." (Proust/In search of lost time vol. 6

p.221) In the theories of Bergson the phenomena described by Proust is

called 'pure duration', "a duration in which the past is big with a present

absolutely new. But then our will is strained to the utmost; we have to

gather up the past which is slipping away, and thrust it whole and undivided

into the present. At such moments we truly possess ourselves, but such

moments are rare." (summarized by Bertrand Russell in his 'History of Western

philosophy'; p.759-760) It has been said of Proust that he was a writer

who put the "greatest interpretive power" in "the smallest image or detail"

(NB 43) and he wrote many pages of exhaustive descriptions of memories

triggered by small incidents, like the often quoted passage of a cup of

tea and a special kind of cooky called 'Madeleine', the tripping on two

uneven pavement stones in front of a coach house and the knocking of a

spoon against a plate by a servant. Proust calls these triggers "chance

happenings" and after describing the scenes they recall he summarizes the

phenomena of such recollections: "...I began to divine as I compared these

diverse happy impressions, diverse yet with this in common, that I experienced

them at the present moment and at the same time in the context of a distant

moment, so that the past was made to encroach on the present and I was

made to doubt whether I was in the one or the other. The truth surely was

that the being within me which had enjoyed these impressions had enjoyed

them because they had in them something that was common to a day long past

and to the present, because in some way they were extra-temporal..." (p.222-223)

Being "outside time" relieves for a moment the "anxieties of death" of

the central figure in the novel, who becomes "an extra-temporal being"

and "therefore unalarmed by the vicissitudes of the future". (p. 223) This

relieving and therapeutic function is beneficial both for the fictional

figure and his creator: "...when we seek to extract from our grief the

generality that lies within it, to write about it, we are perhaps to some

extent consoled for yet another reason () which is that to think in terms

of general truth, to write, is for the writer a wholesome and necessary

function the fulfilment of which makes him happy, it does for him what

is done for men of a more physical nature by exercise, perspiration, baths."

(p.262) Reluctantly Proust poses himself the question whether his undertaking

of writing a book about his past life is not so much for the sake of "the

supreme truth of life" that resides in "art", but a method for consolation.

Thinking about some of his beloved who have died he wonders "whether a

work of art of which they would not be conscious could really for them,

for the destiny of these poor dead creatures, be a fulfilment." (VI p.262)

At an earlier stage in his novel Proust admits that other people are "merely

show-cases for the very perishable collections of one's own mind." (V p.637)

In the same way he observes that his thought uses the products of other

writers "for its own selfish purpose", "as though they had lived a life

which had profited only myself, as though they had died for me". Proust

understands that in return he will be consumed by others: "Saddening too

was the thought that my love, to which I had clung so tenaciously, would

in my book be so detached from any individual that different readers would

apply it, even in detail, to what they had felt for other women." (p.263)

Reading and rereading this passages of Proust

I am thrown back to my own life and the therapeutic function of writing,

my attempts to halt time, even to try to go back in time, after the unexpected

and sudden death of my girlfriend, bitten in her lip by a wasp being with

friends out on a roof terrace on a hot summer evening, by now eight years

ago. She died almost instantly of what the doctors named an anaphylactic

shock. The very night the messenger of doom had visited me I started to

write: "At the cross road of night and dawn this is been written//the dead-line

is alarmingly close//will your funeral appear in time?//You are not deceased,

but dead//still by looking intensively in the mirror I can see your eyes

in mine, talk with you..." I continued to write for several months, mostly

late at night when I would feel most desperate, sitting at my computer

at home both rereading and writing, also in public spaces, during train

travels, in cafes in foreign countries. I would enter also the handwritten

texts into the computer and during some time I would rephrase, and smooth

the text, reading it half aloud to myself. After a while I would not any

more change the text, I got afraid that by polishing sentences too much

my feelings would get lost in the shavings. Fixing my memories in writing

was quietening me, it gave me the feeling that I had halted time, not for

long but just during the process of writing and reading. It was and still

is an almost complete private journal. More than a year later I printed

a few copies and included them in a series of memory boxes containing scrolls

of digitized pictures of memoralia of my girl friend, photographs and a

sound tape of the funeral and samples of her favourite collection of perfumed

soaps. The boxes were covered with pieces of a silk banner with stripes

in my girl friend's favourite colours that had been printed to show during

the funeral. A few close friends did get such a big box with the message

that they need not read the text now, that it was there as a testimony

for later. Contemplating objects related to my beloved, arranging them

in a series of picture scrolls, writing a personal journal, making a limited

set of copies and distributing them, was a way of externalizing my suffering,

it did not stop it but made the pain more bearable. It was a ritual of

sharing grief, finding myself a model for mourning and bereavement, also

keeping track of attempts to make new relations.

"The normal fate of a journal is to be destroyed"

notes Malik Allam in his study on "Journaux intimes, une sociologie de

l'écriture personnelle/Intimate journals, a sociology of personal

writing". (L'Harmattan; Paris 1996; p.7) Allam has tried to shed light

on what normally remains invisible, the intimate diaries, journals of people

who have no intention to publish them, who in most cases do not even show

their content to members of their family or friends. It is a study about

the 'diarist' who retreats to his room to have through his notebook a tête-à-tête

with himself. "Il 's'isole, se resource, reprend contact avec son moi profond.

Ecrivent sa vie, il en devient l'auteur, le démiurge." (p.8) As

a sociologist Allam faced a delicate problem, it is already difficult to

ask someone for the existence of an intimate journal, let alone wanting

to read it and than talk about it. In public collections there are very

few examples of such journals of ordinary, 'non-famous' people, it is often

not even a separate category for the archivist, and the interest of the

Allam was not historical, but to know how such journals are functioning

now a days. The solution was to "interrogate the diarists without reading

their journals" (p.7) and selecting people for such interviews by advertisements,

contacting amateur writers clubs and through 'hear say'. The reasons for

writing and the process of writing differ. Ariane, 57 years old, married

for 30 years with three children, started to write as a young girl of 16

stimulated by a catholic priest to whom she was posing questions about

the meaning of life. She stopped to write at the age of 27 when she got

married and started again when she became 40, in a reaction to long years

of letting herself "obediently be devoured by husband, children and household

tasks". Her ideal is to write every day: "Sous forme d'un flash aigu, percutant,

je voudrais décrire juste l'étincelle qui a fait que cette

journée est différente de celle d'hier ou de demain." She

likes to reread her journals and compare her past life with the daily preoccupations

of the moment. Her husband knows she is writing but respects the fact that

she does not show her journal. Once she had the thought to leave her journals

to her children after her death and immediately catches herself in the

act of self control while writing. (p.35) Catherine, 31 years and single,

has a journal because it is useful, it assist her thoughts and helps her

to understand her own reactions and what is going on in society. She uses

writing as an aid to "resolve bad relations with a person." (p.49) Fanny,

43 years, two times separated and living with her two children, grew up

with a lot of restrictions in an anti-clerical family: "there were things

one was not supposed to say about oneself". She felt like having killed

her fancies, her imagination: "that kind of things I have tried to refind

by writing." At a later stage Fanny goes to a psychoanalyst for therapy

but that does not work. From that moment on she starts to write again for

herself: "je me disais en fait ce que je ne disait pas à l'analyste."

(p....) Though in this study more women come to word than men there are

examples like that of Eric, 67 years who starts only very late at the age

of 57 to write his journal. After a professional life as an engineer, married

with a woman who has the same occupation, both socially well integrated,

his wife gets the illness of Alzheimer and he decides to care for her at

home. As the illness of his wife progresses and his tasks get more heavy

he feels marginalized and gets depressive. During a treatment he is suggested

to start a personal journal as an anti-depressive tool. For several years

he notes the events and ideas of the day. This becomes a relaxing moment

for him, it makes him cope. At a later stage friends from the medical profession

suggest that it would be a good idea to publish selections of his journal.

Eric experiences this proposal as a sign of social acceptance of him in

this marginalized role. There is also a story of a young men who starts

to write a journal to overcome an unhappy love affair and one of an American

student who goes to study in France, feels isolated and also has problems

in a shared student apartment because of him showing his homosexuality:

"I started my journal to have someone to speak to in English". (p.96) Claude,

another man of 47 years, started to write at the age of 19. He says to

have been influenced by reading the journals of Anne Frank and also has

difficulty to fill the emptiness he feels in life. In his journal he writes

about the homosexuality he keeps hidden for the world outside: "He describes

himself as someone who has no love life, but a life with paper." (p.105-106)

For Claude there must have been an association

between the hiding in the 'Achterhuis/Annexe' in Amsterdam of Anne Frank

and her family for the Nazis and the hiding of his own homosexuality. He

mentions Anne's journal as an example for him to follow. He has no intention

to 'come out', show his journal to other people, though the fact that he

participated in the research project of sociologist Allam, maybe a step

in another direction. Writing her diary was a very intimate and private

affair for Anne. There is an interview after the war with Miep, a woman

who helped to hide the Frank family and other jewish people in the annexe

in the centre of Amsterdam, that describes this: "Once [] when I went up

into the Annexe and opened Anne's door, I saw her sitting at a table and

writing in an account book. She was obviously startled, got up and quickly

shut the book". ('The diary of Anne Frank, the critical edition prepared

by the 'Netherlands State Institute for War Documentation'; David Barnouw/Gerrold

van der Straan editors; Viking London; 1989; p.25). Completely different

circumstances from those of Claude, incomparable in hindsight when we think

about the difference in fate, but the starting point is the same: "I hope

I shall be able to confide in you completely, as I have never been able

to do in anyone before,and I hope that you will be a great support and

comfort to me." This is what Anne writes on the front page of her first

journal on the 12th of June 1942, the moment when she starts, like Claude

many years later, a 'life with paper'. As she continues to write in the

almost two years that follow, the dialogues with herself are expanding

to more than one Anne, like in this fragments, one of the last entries

in the diary, just before the combined raid of Dutch and German Jew-hunters

in august 1944 when all those in hiding are arrested: "A voice sobs within

me: "There you are, that's what's become of you, you're uncharitable, you

look supercilious and peevish, people you meet dislike you and all just

because you won't listen to the advice given by your own better half".

Oh, I would like to listen, but it doesn't work." (ibid. p.699) Right after

the arrest Miep manages to pick up and hide the diary from the floor, where

it has been thrown by the invaders who are searching for jewels and money.

The sole survivor of the family is the father of Anne, Otto Frank. Right

after the war he reads his daughters diary in which she also mentions her

idea to use her diary as a basis for writing a book after the war. He immediately

starts to make a transcript and with the help of friends makes the diary

into a manuscript in which a few cuts and alterations are made. After initial

difficulties with almost no publisher interested in the manuscript, it

gets published in 1947. Some more fragments dealing with discovery of sexuality

by Anne are left out on the instigation of the publisher. After a few years

the diary starts to be a world success and has been translated in 50 languages.

With the spreading of this intimate account differences in reading and

interpreting come to the surface. As Proust noted already readers will

apply what is written to their own circumstances. In the case of the Diary

of Anne Frank bitter fights have been fought, about how the published text

relates to the original manuscript. There have been Swedish, French, American

and German publications that claim that the diary was a hoax, all of them

from ultra right wing circles. This has led to court cases because of slander

and denial of the holocaust. It even led to forensic research on the original

diaries, taking samples of the glue of the bindings and handwriting identification

in all detail, like a comparison of the shaping of the letter 't' as written

on different dates in the diary. Other conflicts have risen over the adaption

of the diary for film and theatre. One of the fiercest opponents in this

field was not a right winger but the American author Meyer Levin, son of

Jewish immigrants from Lithuania, a man who first proposed to Otto Frank

to promote the book in America and also wrote a theatre adaption, not staged

because a later Hollywood style version was judged to be more suitable.

In his adaption Levin changed the emphasis from the universal lesson of

tolerance and anti-discrimination as promoted by Otto Frank to one of teaching

Jews how to be good Jews. In a review of a few studies dealing with this

long lasting conflict for the New York Review of Books, the Dutch author

Ian Buruma writes: "Since it contains so much, readers get different things

from the diary, just as they would from any complex work", in the end "Everyone

wants his own Anne". (NYRB...)

|

|

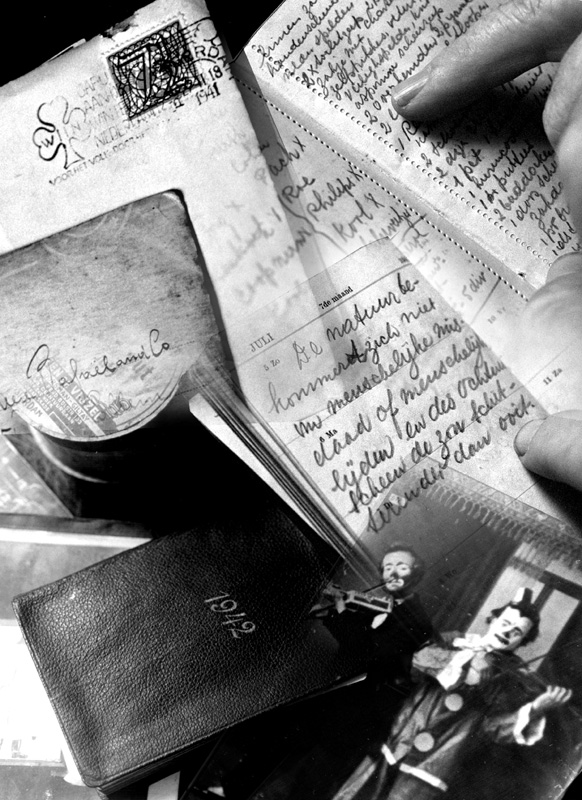

The house I live in was also used as a hiding

place for Jews during the war. It is situated on the edge of the Jewish

Ghetto as it was established in 1941 in the inner city of Amsterdam. I

live here for 23 years and it must have been two decades ago that while

cleaning the attic that I found in a crevice between the roof panels and

their supporting wall a series of dusty packages in what once might have

been brown wrapping paper, containing some personal papers, an agenda,

a passport, crinkled photographs, pieces of soap, a package of shaving

blades, two lipsticks, a bag with tallow powder and a small box with coffee

beans. All these things belonged to L.C., a Jewish man who apparently had

been the owner of a music shop and also performed as a kind of clown, as

could be seen on some of the photographs and which explained the make up

utensils in the packages. Of course I did read and reread all the documents

and the notes in the agenda, trying to make sense of it. It hardly did.

Especially the notes made in the agenda (a pocket agenda of the year 1942

published by the Dutch branch of Siemens in The Hague) were difficult to

understand. It is not clear whether they have any connection to the day

sections in the agenda, and their content is most puzzling. There are many

single sentences with almost commonplace content in an exalted style, like:

"I do not maintain that I usually frequent such kind of establishments"

(sunday January 4. 1942) directly followed by "Autumn hues did show themselves,

fields became naked" (monday January 5. 1942). While writing this article

on personal memoralia I felt the urge to look once more at these traces

of people who lived in the same house as me. Up to the attic, finding the

dusty archive box that functions as a sanctuary for their souls. Again

I am reading the agenda of 1942 and as I skip over sentences that seem

to have no relation, now and than I find some that express, over the subsequent

pages, despair, agony and fear: "That they were people who acted in horrid

gravity"; and "a sinister suspicion flashed through his brain"; and "he

was allowed to stay, true only conditional, but still he was allowed to

stay"; and one of the last entries "Nature does not care about human crime

or human suffering and that morning the sun was shouting more brilliant

than ever". This last sentence is written on a page that opens with sunday

the 7th of July 1942, so maybe there is a meaningful chronology after all.

The rest of the agenda pages remained blank, only in the back, where there

is place for addresses and notes, are some scribbles. One is a list of

recipes that should be acquired, goulash, macaroni, pancakes with marmalade,

... and the very last page is a packing list. Again I shiver when I read

the very small and neat handwriting with over 30 things 'not to forget'.

I need not list them all: "small linen bag with darning wool, nail brush,

padlock, safety pins, tooth paste, shaving cream, 2 pyjamas, 2 shirts,

2 towels, writing equipment, 5 pair of socks...." Maybe, in all, I have

looked five times at these memoralia, and each time I am so shocked. I

did not dare yet to try and see if this man or any of his relatives survived

the destruction machinery aimed at them. Being an archivist myself, the

last thing I would do is adding these humble traces to the huge cemetery

of the State War Archives or whatever institute that is professionally

accumulating human misery. As long as I live in this house, these disintegrating

objects and dusty papers might better remain here so I can regularly pay

my respect to L.C. who is still sharing his house with me.

"In the attics of homes all over the world, in

the backs of cabinets and bottom of drawers, lie testaments to the lives

of many forgotten women. Scrapbooks, books constructed of the scraps of

lives, () multi layered records of life experiences." These are the opening

sentences of a draft text on 'scrapbooks' by Georgen Gilliam which I found

on the Internet while searching for sources for the tales on personal memoralia

you are reading now. Gilliam is specially interested in personal scrapbooks

by women containing ephermal mementos of a woman's life: "letters, photographs,

clippings, invitations, locks of hair, dance cards". () Often there is

not much written text in such collections of documents and objects, kept

together in a book as a proof of personal experiences and relationships.

These scrapbooks may be occasionally shown to others but mostly in an intimate

and personal atmosphere. It is during such showings that the meaning of

the objects and documents will be told, though some scrapbooks might haven

written captions. Georgen quotes many recent studies on the subject, often

from a feminist perspective in which the exclusion of this femine form

of expression from literary and historical studies and the lack of understanding

of gender differences in self-representation is noted. When compared with

the favourite male form of self-expression the autobiography "a lack of

self-focus" can be noticed in the scrapbooks by women. "They are often

a legacy for a woman's family, the creatrix in the role of the family historian."

There are several references to the making of 'quilts' by women, a traditional

artwork "constructed out of pieces of clothing, scraps and bits gathered

from the outgrown garments of a woman's family", and the analogy with the

way these scrapbooks, and women's autobiographical writings in general,

are composed. The observations of Estelle Jelinek, who studied women's

autobiography, on the difference between male and female auto-biography

have a direct link to this: "From earliest times, these discontinuous forms

have been important to women because they are analogous to the fragmented

and interrupted, and formless nature of their lives." (Estelle Jellinek/Women's

autobiography; p.19) Another mostly femine form of quilt like construction

is the 'Poesie album', still very popular in Germany and the Netherlands

were it developed in the 18th century as a companion for young girls, an

album in which friends, family and acquaintances from school would write

little poems, stories, wishes and wisdoms, would draw picture or donate

sticker like pictures for adorning its pages. In an abundantly detailed

study on the 'Poesiealbum' by Jürgen Rossin an attempt is made to

rehabilitate this stereotypical text form with its subjects of worldly

wisdom, virtue, friendship, religion and children's rimes. There would

be entries like "Das lachen ist ein Macht, vor der die Grössten dieser

Welt sich beugen müssen" or "Das ist ein Land der Lebenden und ein

Land der Toten,//und die Brücke zwischen ihnen ist die Liebe//das

einzige Bleibende, der einzige Sinn." (p.401) Maybe such texts might sound

quiet heavy for young girls of our times, but I am sure that when one would

analyze some of the texts of 'heavy metal' bands, that are extremely popular

with young girls now, a similar tone can be found. The Poesie Album is

a book that will be presented by its owner to others to write down new

entries in them, it is meant to be read and reread to internalize its content.

Rossin concludes his study with a statement in which he points to the value

of these albums as a means by which human ties can be kept over time and

sociability/Gemeinschaft can be documented through the use of maximes and

captions. In his view these albums are more than just kitsch like, nostalgic

or fashionable products, though in the end they are often lost when a girl

grows older, as a 'Poesie rime' is documenting: "Hier schreibe ich mich

ins Büchlein ein, weil ich nicht will vergessen sein.//Noch lieber

aber will ich im Herzen stehn,//weil Büchlein oft verlorengehn." (p.343)

We can even go further back in time to find examples of similar usage of

personal notebooks, like 'scrapbooks' and 'poesie albums', in the 'hupomnemata'

of the Greco-Roman culture: "One wrote down quotes in them, extracts from

books, examples and actions that one had witnessed or read about, reflections

or reasonings that one had heard or that had come to mind. They constituted

a material record of things read, heard, or thought, thus offering them

up as a kind of accumulated treasure for subsequent rereading and meditation."

This is part of an article by Michel Foucault, "L'écrire de soi/Self

writing", in which he describes how this form of writing an reading was

not so much "a narrative of oneself" but a collection of "what one has

managed to hear or read" with the aim of "the shaping of the self" and

he quotes Seneca on its function: "We should see to it that whatever we

have absorbed should not be allowed to remain unchanged, or it will not

be part of us. We must digest it; otherwise it will merely enter the memory

and not the reasoning power." (p211-213) While writing this essay I am

of course constantly confronted with the problem how to find a balance

between neatly quoting from others, and reformulating what I have taken

from others, but what in my feeling has become something from myself. Often

the distinction between the two blur. You can only create yourself through

the others, no divine creation out of void, it is more like an endless

reconfiguration of what existed already, but there are so many elements

that I myself and others might be under the impression that something unique

or new has been created.

"La lutte doit continuer entre cette part de la

parole qui tend passionnément à la diffusion le plus large

et une parole qui au contraire veut s'enfoncer, rester dans un cercle étroit,

descendre même dans l'intimité de l'individu, pour le séparer

de lui-même par le moyen de ce qu'il a de plus collectif, de plus

universel, de plus inpersonel, le langage." This is the concluding sentence

of another study on this subject: "Les baromètres de l'âme,

naissance du journal intime/Barometers of the soul, birth of the intimate

journal", by Pierre Pachet. It is unescapable, once the intimate is made

public it will become something of another order. Writing because of the

need to tell yourself to the others, mostly unknown to you. Reading because

you have a need to identify with someone else, or you just like to observe,

being invisible yourself. There surely is a strong element of voyeurism

and its opposite when the intimate is made public.

There are also intimate writings, pictures not

consciously made public, things one sometimes finds by chance: your heart

starts to beat a bit faster, blood flushing to your face, you look and

read, feel somewhat ashamed entering the private world of someone else,

but still, you will read on... It must have been 1963 when during one summer

I lived in a squatted house in the city of Haarlem, while attending sculpture

classes at a new experimental art academy. It was an old 17th or 18th century

house at the river in the centre of town and with a friend we were staying

in a kind of attic, were apparently lots of other people had drifted by.

Between the rubble I found a notebook with a series of letters describing

an adventurous travel of a man and his girlfriend through the North of

Africa. Apparently the letters in the notebook were never send. I have

forgotten the details of those letters but not the thrill it gave me to

read something that was not meant for me. Seven or eight years later a

similar thing happened, also related to belongings left in squatted houses.

This time it was in the Nieuwmarkt neighbourhood in Amsterdam at the high

time of the hippies making their pilgrimage to the 'magic city'. I still

see the hoards of long haired rucksack tourist who would ask "were are

the abandoned barracks", as the word had spread in the whole of Europe

that there was an area in the centre of town with houses, just for free.

The sounds of bongo's and cheap bamboo flutes were mingling with the smell

of marihuana and sometimes the siren of the fire brigade mixed in, when

not well tended, fires started to devour a house because half stoned city

nomads were trying to bake pancakes on an open fire in the middle of a

wooden floor. Such incidents and the introduction of heroin in the area

by American motorbikers in combination with some opium trade to outsiders

by a few Chinese dealers, let to regular razzias in the squats by the local

police in search for illegal drugs and unwanted foreigners. That is how

I found a collection of letters, photographs and hallucinatory drawings

left by some Italian hippies. There were some postcards meant to be sent

to their families, way back in the deep south of Italy, in which they explained

why they had left home and what freedom they were searching for. It must

have been these incidents that have pointed me the way to another profession

than that of a sculptor, that of an archivist of modern social movements,

whereby my greatest interest have always been to acquire personal archives,

be it during someone's lifetime or as often happens posthumous. The ceremonial

in which this transfer from the private to the public is realized often

has a strong schizophrenic character, on the one hand the person in question

or his or her heirs are full of how important for posterity it is that

everything will be made available to researchers and the public and on

the other hand whole lists of restrictions are proposed to the archive

institute to control the content of possible representations to be constructed

from this material. There is also the silent disappearance of certain letters,

photographs, books, I had noticed during a first visit in a preliminary

stage of negotiations, taken away by a self-appointed censor who will give

no explanation and often, as an archivist confronted with the heirs of

a deceased person, one feels not in the position to ask for the reason

why. I remember an extreme case of a political and literary figure who

had already published some of his diaries and was handing me the original

not before, right under my eyes, he tore out a few pages. Why this drama?

He had told me already that he had omitted some parts, in the published

journal, he found too emotional and personal. He could have easily tore

out the pages before I arrived, so I would not have known. Maybe this ceremonial

act was symbolic prove that any biography or other representation of a

person by others can not be more than a mosaic on the basis of incomplete

information, that identification and imagination of a biographer is needed

to cement fragments in a portrait that seems real enough. An analysis by

Nelson Goodman, though made for the visual arts, still very well applies

here: "..a picture, to represent an object () must be a symbol for it,

stand for it, refer to it; and () no degree of resemblance is sufficient

to establish the requisite relationship of reference. Nor is resemblance

necessary for reference; almost anything may stand for almost anything

else. A picture that represents () an object refers to and, more particulary,

denotes it. Denotation is the core of representation and is independent

of resemblance." (Nelson Goodman "Languages of art, an approach to a theory

of symbols", Oxford University Press; London; 1969; p.251)

"I have resolved on an enterprise which has no

precedent, and which, once complete, will have no imitator. My purpose

is to display to my kind a portrait in every way true to nature, and the

man I shall portray will be myself." These are the famous openings sentences

of "The confessions" by Jean-Jacques Rousseau a text describing his own

unique life from birth in 1712 to the year 1765, displaying himself "as

I was", both "vile and despicable" and "good, generous and noble". Though

he did read parts of this text to small audiences in 1771 it is only three

years after his death in 1778 that his Confessions were published. Rousseau

is seen by many as the creator of a new genre, the auto-biography, which

seems nowadays such a natural form of expression, but it took several centuries

of silent and slow development before the writing of intimate diaries and

journals developed into this literary genre. Early examples like the 4th

century "Confessions" of Saint Augustine, bishop of Hippo in Roman Africa,

are different from the self-centred writings and personal display of Rousseau.

Saint Augustine's confessions tell about his conversion to Christianity

after a turbulent youth and the autobiographical elements in the text are

mere background for his mystical experience of finding God. There have

been of course many writers before Rousseau who did dully note the events

of the day, chroniclers who registered with the pace of the calendar what

they witnessed, but this differs from the writer of a personal diary who

tries to capture how she or he experiences personal change. The French

writer Montaigne can be seen as a forerunner of Rousseau, living two centuries

earlier and developing a literary form he called 'trials', 'essais'in French:

"la pensée spontanée de son auteur, mais sur sa personne

même, saisie dans sa dimension la plus quotidienne, la plus privée,

la moins surveillée." (NB 22) Montaigne does write about subjects

like 'idleness', 'on the power of imagination', 'on friendship', 'on smells',

'on presumption', 'on repentance'. Most of the time his own person is not

directly the subject of his writings, but because of this indirectness,

this way of 'denotation', we have the feeling to get a better picture,

with a better resemblance of the man Montaigne than the one we get from

the self-centred, more realistic writings of Rousseau. "Most autobiographers

are anxious to build up a personality, to present themselves as more consistent,more

resolute, more far-sighted, and built on an altogether grander scale than

they would have appeared to their wives or their intimates." This observation

is by the English translator of the 'Essays' of Montaigne J.M. Cohen, who

compares, the writings of Montaigne with those of Rousseau. He sees the

Confessions of Rousseau as the classical example of a "false portraiture",

with Rousseau "pretending to emotions that he never had", a man thinking

that his "romantic ego was really in control of events" and in the end

was not able to "explain away" incidents "in which he fell short of the

ideal picture of himself". In contrast Montaigne does not have the need

to explain his action "he merely notes them down". In the words of Cohen

his personality is "a kind of observer which, although incapable of controlling

the complete mechanism of his life, is able to prevent its springing too

many surprises on him".(p.12) The writing of essays gave Montaigne some

self control, an example of which can be found in his essay "On idleness",

were he describes how he tries to find rest in retirement, leaving his

mind "in complete idleness to commune with itself". This does not work

out as his mind starts to behave "like a runaway horse", "hundred times

more active on its own behalf than it ever was for others". Montaigne gets

haunted by chimeras and imaginary monsters and notes how "in order to contemplate

their oddness and absurdity": "I have begun to record them in writing,

hoping in time to make my mind ashamed of them". (p.28)

This theme of writing to shame once own mind,

to control oneself, is an old one, it can be found with another bishop

from the same century as Saint Augustine, the bishop of Alexandria, Athanasius.

Michel Foucault quotes a text of Athanasius on the indispensable elements

of the ascetic life: "Let this observation be a safeguard against sinning:

let us each note and write down our actions and impulses of the soul as

though we were to report them to each other; and you may rest assured that

from utter shame of becoming known we shall stop sinning and entertaining

sinful thoughts altogether. Who, having sinned, would not choose to lie,

hoping to escape detection? Just as we would not give ourselves to lust

within sight of each other, so if we were to write down our thoughts as

if telling them to each other, we shall so much the more guard ourselves

against foul thoughts for the shame of being known." (quoted in Michel

Foucault; article 'Self writing', part of a series of studies "the arts

of oneself" in "Ethics/Essential works" Volume One; Allan Lane/The Penguin

Press; 1997; p.207) This proposed daily writing exercise could take only

place on the basis of the 'impersonal' and 'collective' device called language,

it was a strict private exercise, not meant to be shown to others and still,

when writing one had the feeling to be open to the gaze of others, or as

Foucault formulates it: "the constraint that the presence of others exerts

in the domain of conduct, writing will exert in the domain of the inner

impulses of the soul." (ibid. p.208) Expressing one's thoughts in the device

of 'language' implies adapting to the embedded value system of the cultural

group that uses that language. One might feel free to use any language

construction that comes to the mind, but in the end freely moving thoughts,

not having any substance yet, need to be cast in the mould of an existing

language to be fixed in writing. It is in that process that though alone,

one is not really alone, while writing 'the others' are always looking

over your shoulder. One wonders if the writing down of haunting images,

of devilish thoughts would have an auto-cathartic effect, would function

as a purgative medicine that drives out the dark forces within ourselves,

a 'katharsis' effect, an act of 'self-art' were one is author, actor and

audience at the same time, thus realizing the classical idea as formulated

by Aristotle in his treatise on tragedy, the 'Poetics': "..through pity

and fear effecting the proper purgation of these emotions". (EB 13; p.14/1b)

In our time we happily go around in the ghostly labyrinths of the inner

souls of other writers, who apparently did not constrain themselves, be

it De Sade, Lautréamont or Nietzsche, unhindered by the never ending

academic debate whether this soul-hiking is just an aesthetical pleasure

for the sake of art only, outside the current of ordinary human feeling,

or that such darkish expositions will awaken our emotions, will learn us

something which is applicable to our own lives. (for a longer expose of

this debate see EB 13; p.14-15)

The writer may show his deepest self to the reader,

but apart from the professional critics, the academic discourses and fan

mail the reader remains invisible for the writer. "Why can I not see the

face of my reader through these seraphic pages" writes Lautréamont

in his "Chants de Maldoror" and he laments the "opacity of this sheet of

paper" on which he is writing being "the most formidable of obstacles".

(quoted in Alex de Jonge "Nightmare culture, Lautréamont & 'Les

chants de Maldoror'"; St. Martin's Press; New York; 1973; p.165) It is

in personal correspondence that writing paper becomes transparent. We have

an image of the other while writing, and can see ourselves when we read

what we just have written. A letter thus becomes looking glass, mirror

and telescope at the same time. I think that the personal letter, the correspondence

between two people is one of the most constant forms of expression through

history. "To write is thus to 'show oneself', to project oneself in view,

to make one's own face appear in the other's presence. And by this it should

be understood that the letter is both a gaze that one focuses on the addressee

(through the missive he receives, he feels looked at) and a way of offering

oneself to his gaze by what one tells him about oneself." This is Michel

Foucault summarizing classic ideas on letter writing by Seneca and Demetrius

(p.216) and it sounds like a contemporary analysis of the writing of letters

twenty centuries later.

I am a writer of letters since the time I was a boy. In the beginning I was forced to write these regular letters to my aunts, uncles and grandmother, but soon I developed a taste for it and enjoyed the exercise. I even had, as a boy, sparse correspondence with my father who I did not see for more than ten years because of a bad divorce.

So in a way I learned to show myself in writing to people I knew and people

I did not know. Writing letters have helped me when travelling alone and

studying in other countries, to overcome feelings of loneliness and most

of all to canalize the waves of emotion in relationships with women. There

were travels, friends, a circle of international contacts, myself living

in other countries, my girl friend finding work on an other continent,

me staying behind for many months, all letter producing circumstances.

I still prefer to write my personal letters by hand, the direct notation

of a flow of thoughts, no backspace or delete button as on a each correction

or rephrasing visible, with only the radical option of crumpling up a letter

and a fresh start. Such a collection of manuscript memoralia is only half

a collection, the self, the other half stays with the addressee, and it

is only through the sad circumstance of people dying that some of my own

letters have come back to me. Such dramatic moments have pushed me to read

some letters again. Normally all this correspondence resides in binders,

nothing but a warehouse of memories, somewhere in the attic. I rarely look

at them, it is sufficient to know that they are there, traces of my life

that will enable me to go back on the trail whenever I wish to do so.

Electronic mail has made correspondence more easy,

one can send mail to one or more addressees in a single gesture, the speed

of delivery is almost instant, the number of people one regularly contacts

increases, but there are differences with the now old fashioned ways of

handwritten correspondence. The final fixity of the text when one composes

the initial electronic letter is still there, but when one gets a reply

something changes. We often get our whole letter or parts of it back in

replicated form, marked with some graphical signs, with only short answers

after each particular section. Such business like efficiency can have a

deadening effect on the quality of our communication, as we are missing

the selective rephrasing by the other of our own observations, remarks

and questions, seeing ourselves in a mirror through the answer of the other.

The speed of communication makes our letters shorter, the exchange of letters

more dynamic, with the system of on line 'chatting', interactive writing,

as the ultimate written communication form after which we enter another

realm, that of telephony. On line chatting, a dialogue over computer networks

through keyboard typing, is a way of communication that normally doesn't

leave traces, except when one keeps a so called 'log file' open which will

capture the complete content of a chat session. That is almost on the same

level as taping our telephone conversations, and telephone taping easily

leads to telephone tapping. As long as we are not into black mailing or

preserving our role as a president of a big firm or a country, it is something

that is 'not done'. Of course we will remember our personal conversations,

not as proof of law, but through the inconsistent and biased properties

through which our mind wishes to remember them.

Dematerialization of electronic communication

diminishes the amount of traces that are left, hence the memory function

such forms of communication can have. For next generation there might be

less personal traces left from the end of the 20th century when the evaporating

telephone, fax, email and other electronic communication systems took over,

than from the three previous centuries when written and printed communication

in ink on paper was more widely used. It is possible to keep 'back-up'

copies of electronic documents, but their invisibility, their need of the

right kind of equipment and software to make the content of a floppy, tape,

CD-Rom, Zip-cartridge or whatever other form of electronic information

carrier, audible or visible, the fact that the content of these back-ups

can not be spatially spread out for evaluation and deselection, that the

only access to these electronic documents is through the small window of

a computer screen, means that many of these indistinct back-ups of our

memories will be easily lost or thrown away, because one did not realize

any more what was on it. In a way we are partly moving back to ancient

times when notes for daily use were written on clay and wax tablets or

black boards that could be reused, as more permanent writing materials

were not abundantly available. Erasing or wiping of the writing surface

for reuse as in ancient times, has been superseded by the regular deletion

of digital information in modern times.

Engraving and writing, have always been used in

metaphors for the way we remember, how we externalise what was on our mind,

how we make a prosthesis for the mind, create 'artificial memory'. It is

found in our daily language: something is "engraved" or "impressed on my

mind", "stamped on my memory". And with the changing over time of the technology

of making notes, of depicting and recording, metaphors for remembering

are keeping pace, from impressing a seal into wax, to writing with a pen

on paper, painting a picture, photographing, recording with a phonograph,

film, video, using a computer. The latest, multi media, computer is a device

which allows us to create almost unlimited image surfaces and sound events,

representing texts, sound, still or moving images, or combinations thereof.

For many people there is a similarity between the working of their own

mind and the coding and decoding processes that form the basis of the functioning

of a computer. At the beginning of this century Sigmund Freud used in a

similar way a device that was called a 'Wunderblock', a 'magic writing

pad', as a metaphor. They still exist as a children's toy in a more modern

form with plastic sheets and carbon paper instead of mica and wax: a small

frame with a transparent top layer, an opaque middle, and a black layer

below; on the spots were one writes with a stylus the layers will be pressed

together and the writing becomes visible; by separating the layers again,

through moving a strip between them, the text disappears from the surface,

but physically the traces still exist in the lower black layer where in

time they fade away because they are overwritten. In the words of Freud:

"Denkt man sich,dass während eine Hand die Oberfläche des Wunderblocks

beschreibt, eine andere periodisch das Deckblatt desselben von der Wachstafel

abhebt, so wäre das eine Versinnlichung der Art, wie ich mir die Funktion

unseres seelischen Wahrnehmungsapparats vorstellen wollte." Freud also

uses another metaphor of the mind whereby he sees himself as an archaeologist

who studies an imaginary Rome, the city with a long and copious past, "an

entity () in which nothing that has once come into existence will have

passed away and all the earlier phases of development continue to exits

alongside the latest one", a Rome where one could admire the Coliseum and

at the same time the "vanished Golden House of Nero" that once stood at

the same spot. Freud uses this unimaginable and absurd fantasy to explain

the difficulty "to represent historical sequence in spatial terms", because

"the same space cannot have two different contents" and he concludes: "It

shows us how far we are from mastering the characteristics of mental life

by representing them in pictorial terms". (p.226) It is good to point to

the shortcomings of this kind of metaphors, but we can not do without such

analogies, such visualisations when we want to represent the invisible

workings of our own mind. Freud has had a life long obsession with archaeology

and there is a strong parallel between his interest in this subject and

the development of his theories. The "clearing away, layer by layer, of

the pathogenic psychical material" compares with the technique of excavating

a buried city. The archaeologist uncovers objects, dates them, reassemble

them and tries to place them back in their original context, in much the

same way as the psychologist tries to uncover the past of his patients.

() Freud was also collecting archaeological objects, his working spaces

in Vienna were filled with them. He started to collect after the death

of his father, in 1896 when he went through a period of self-doubt and

self-analysis. These antique objects,mostly rings, scarabs and statuettes

were comforting him in this period of grief and he continued the collection

till his death when it had grown to over 3000 pieces. Already in 1895 Freud

had analyzed why old maids keep dogs and old bachelors collect things like

snuffboxes, the first as a substitute for a companion in life and the latter

for his need to make a "multitude of conquests". Freud observes something

that is also applicable to himself "every collector is a substitute for

a Dun Juan Tenerrio", and concludes these kind of things are nothing but

"erotic equivalents". () To many of us now such an analysis is too much

a value judgement, there is an implicit hierarchy in it, as if there exists

an accepted standard of which personal and emotional relations are good

and which are bad, we might nowadays feel more comfortable with the acceptance

of a wide variety of relational forms, not just between one human and other

humans, but also between humans and any other object of affection they

choose.

Personal memoralia can be almost anything, it

need not be relics that have been part of, or were in touch with those

who were close to us, spaces we lived in, places we travelled to, personal

fortune and misfortune. We also can express ourselves through the collecting

of objects we fancy, things we choose as personal representatives. It can

be artworks, any kind of antique objects, books, gramophone records, cd's,

videos, post stamps, coins, match and cigarette boxes, sugar bags, wrist

watches, empty or full wine bottles, furniture, houses, cars. Depending

on 'your class', the money you can spend and the amount of space you have,

it can be 'real things', replicas, reproductions or small scale models,

though the last type of objects do have an extra function, giving us a

feeling of being in possession and control like a giant, a king of the

toys, a god like master of a miniature world. Many people find comfort

in collecting objects because one is able to gaze at them, without them

gazing back at you. The french writer Jean Baudrillard observes this kind

of relationships with another collection item, pet animals, in his article

on "the system of collecting". He extends this relationship to any other

collectable object and following Freud's observation in 1895 he writes

in 1994: "This is why one invests in objects all that one finds impossible

to invest in human relationships. This is why men so quickly seeks out

the company of objects when he needs to recuperate." (Jean Baudrillard;

NB p.14) Some even say that collecting is the chief mode of our culture:

"not politics, not religion but collecting". (Sarat Maharaj/NB p15) It

is interesting to note how the human urge to collect is represented as

an elementary human faculty, in the literature on the history of the modern

museum, like Reinhard Brandt did in his contribution to a recent congress

on museology: "Wer nichts sammelt, kann nicht leben, sondern regrediert

zur Materie und wird selbst gesammelt." A collection always needs to be

more then one thing, knowledge is based on comparing and ordering of different

things: "Zur Erkentntnis bedarf es die Sammlung". (NB p51) There are others

who even specify the dynamics of such creation of knowledge "the plenitude

of taxonomy opens up the space for collectibles to be identified, but at

the same time the plenitude of that which is to be collected hastens the

need to classify." () Baudrillard puts the emphasis somewhat different,

focusing on the egocentric needs of the individual who is not searching

for knowledge but for himself: "The singular object never impedes the process

of narcissistic projection, which ranges over an indefinite number of objects:

on the contrary, it encourages such multiplication, thus associating itself

with a mechanism whereby the image of the self is extended to the very

limits of the collection. Here, indeed, lies the whole miracle of collecting.

For it is invariably 'oneself' that one collects." (Jean Baudrillard; NB

p.14)

Of course such a collection of signs, semiophores,

personal treasures, souvenirs, kitsch and tat, diaries and letters, or

any other kind of collectibles that we use directly or indirectly to express

ourselves, could remain exclusively intimate and private with us secretly

or in seclusion perusing these memory objects and recalling inwardly their

stories. More often such objects are on show in a house or displayed on

special occasions to other people. Now there is a difference between objects

tugged away in albums, boxes, binders, drawers, cupboards, cases, private

rooms, or less frequented spaces of a house like the attic, and a more

open display in the living quarters, on the wall, on the mantelpiece, the

sideboard or in a glazed cabinet or showcase, or something as luxurious

as a private gallery. The hidden objects need a special occasion, a ceremonial,

to be displayed, their stories to be told. The impact of such infrequent

showing of personal memoralia and the accompanying story telling is more

strong than with objects that are on show permanently. Their known histories

are shared by the members of the household and friends and, over the years,

these stories get standardized and meaning will wear away. Only new visitors

to the house, who wonder about this display of objects, create a fresh

opportunity for the stories to be told again. One could say that these

objects on display are the attributes of a storyteller: "people who like

to recount their adventures () a strange race () who feel half cheated

of an experience unless it is retold". (Anne Morrow Lindbergh/NB 36)

Remembering is not only an act of the will, often